Educational initiative aims to create cultural safety for Indigenous patients and families at Misericordia hospital

June 19, 2025

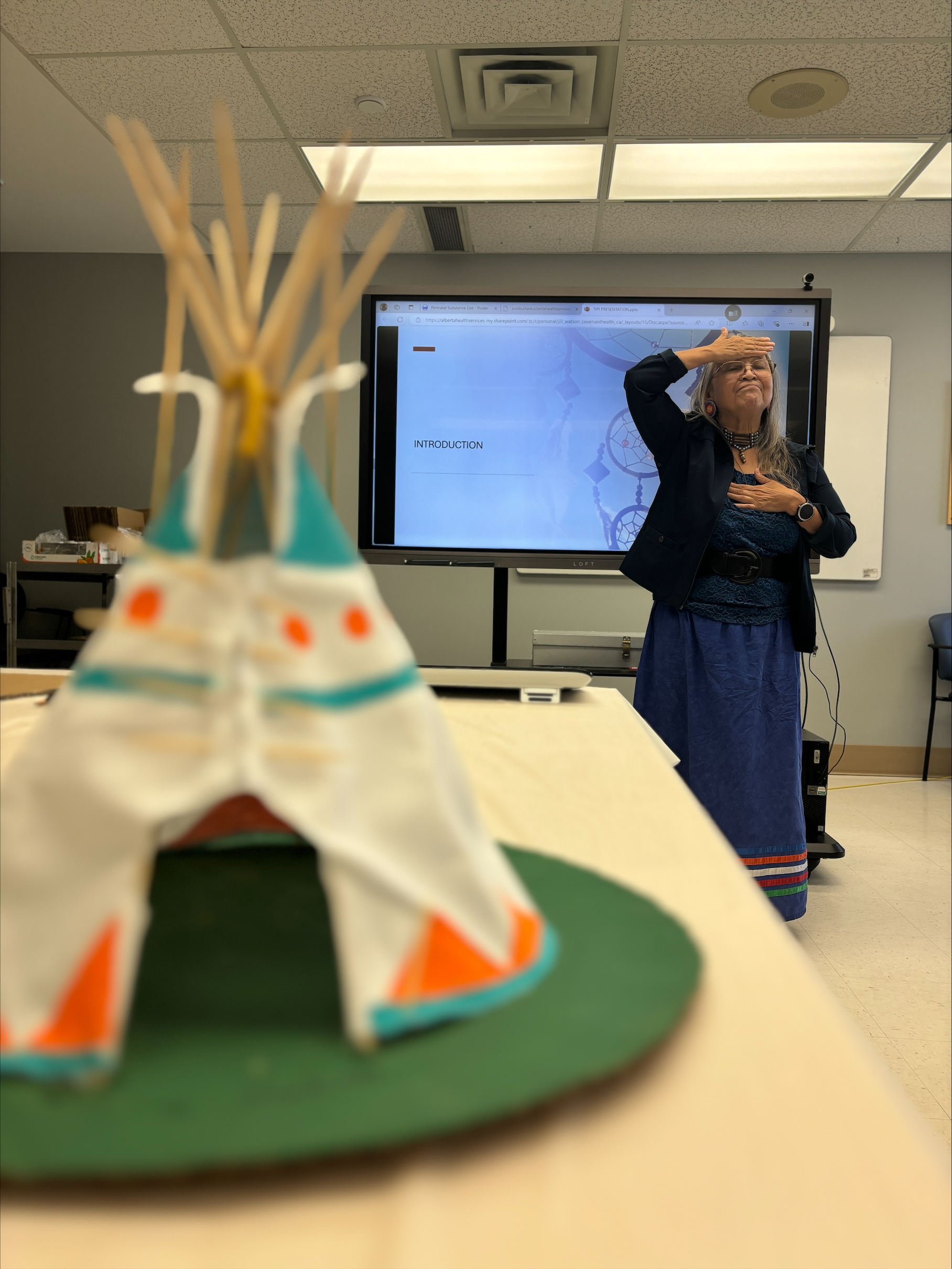

Last fall, when Barbara Derrick, an Indigenous artist and educator, presented her Tipi Teachings sessions to rooms full of nurses who work with postpartum patients and in labour and delivery, she brought a message that was anything but simple.

“The tipi resembles a woman wearing a dress like a ribbon skirt. Her feet are planted on the earth. She is connected to the energies of the earth and of the sun. That is medicine, and it’s important that she take care of herself so she can nurture others.”

Barbara’s sessions were part of an educational initiative within the Women’s Health program at the Misericordia Community Hospital that aims to help staff provide a welcoming space for Indigenous patients and families by giving them opportunities to explore the history, culture and lived experiences of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. What began as a conversation about how to create an Indigenous birthing space has grown into a multiyear journey of learning, listening and relationship-building inspired by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action.

“Because of where the Misericordia hospital is located, we serve a lot of Indigenous patients and families, and we wanted to create a space where they feel safe, recognized and supported,” says Michelle Stadler, program manager for Women’s Health. “It started with wanting to create an Indigenous birthing space, but through our Indigenous community partners, we realized we had a lot of learning to do first. Truth comes before reconciliation.”

For the Women’s Health leadership team, that learning began with development of a land acknowledgment for the Women’s Health program working with Amber Ruben, Indigenous health equity and reconciliation consultant for Covenant Health. Since then, with funding from the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Edmonton, the team has hosted a series of Indigenous-led historical knowledge sessions, workshops about trauma-informed care, storytelling and hands-on activities, inviting staff to see their work, and the people they care for, in a new light. It has also incorporated Indigenous learnings in all Women’s Health staff meetings and annual educational blitz days.

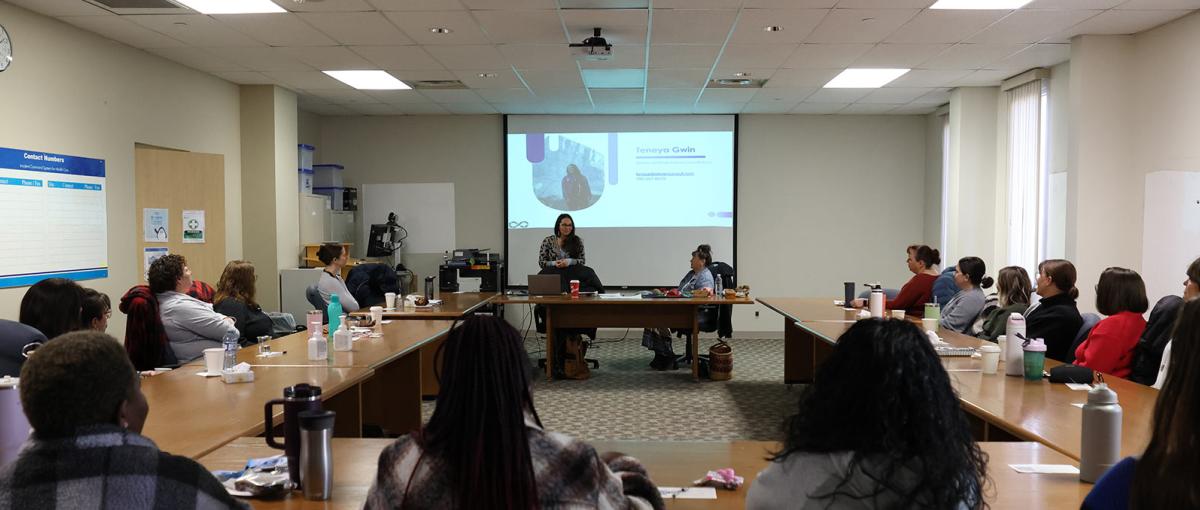

In the historical knowledge sessions, Dr. Carola Cunningham and her daughter, Teneya Gwin, both Indigenous educators, walked participants through the history of colonialism in Canada — from the Indian Act and treaties to residential schools and the Sixties Scoop. The sessions began with ceremony and included teachings on Indigenous worldview, natural law and how past trauma continues to shape Indigenous experiences in health care today.

"It’s very eye-opening to individuals to understand this history and the cultural, spiritual side of Indigenous people. What I hope people take away is that Indigenous people may respond differently to institutions and it’s because of this history. "

Indigenous educator

Teneya’s goal for the sessions was to encourage further learning and to create a safe space for asking questions without shame or blame. “We’re here to answer the questions you’ve always wanted to ask but never had the right opportunity or space for,” she says. “I’m happy to answer any question, as long as it comes from a place of kindness.”

For leaders like Jill Watson, clinical nurse educator for the postpartum unit, the impact of the Indigenous knowledge sessions was clear. “They were hard truths to hear, but I think some of the knowledge people gained from those sessions will live with them forever,” she says.

Jill saw similar reactions from staff during the Tipi Teachings sessions she organized with Barbara for the postpartum unit’s annual education blitz days. In Barbara’s sessions, each participant created a small tipi while learning about some of the teachings behind its structure.

“We associate the designs on tipis with things in nature like the sun, moon and stars,” says Barbara. “There is a story in every design, and the design is owned by the family that lives in the tipi. For example, the colour red is spiritual, and black could signal a transition like a death.”

Barbara hopes that her presentation made a difference and that what she shared can be used. “It’s a journey from head to heart when we do this meditation,” she says. “The information is new, and when we celebrate by creating something together, there’s a connection.”

Barbara Derrick, Indigenous artist and educator, shares teachings about tipis that have been handed down through generations..

Mandi Onic, a licensed practical nurse in the postpartum unit who participated in a Tipi Teachings session remembers how meaningful it felt. “Everyone made their tipi differently,” she says. “It reminded me that we all experience things differently and that we need to ask more questions. How can you empower somebody if you don’t know what is important to them?”

Michelle and the leadership team are beginning to see signs that the education is changing how staff deliver care. For example, the postpartum and labour and delivery units have purchased smudging kits, and staff are now supporting smudging — an important Indigenous cultural and spiritual practice — which can take place right in a patient’s room. “Prior to this work, if a patient asked to smudge, oftentimes the response was no,” says Michelle. “For me, seeing this (change) on the units is huge.”

Small but significant changes are appearing in other ways, too. “The conversations are starting to change,” says Michelle. “And I’m seeing people pause before making assumptions.”

Response to the Tipi Teachings sessions and other workshops has been “resoundingly positive,” says Michelle. Staff interest and participation have grown with each session, and the leadership team has been able to open up some of the programming to other Misericordia staff and to staff from other Covenant Health sites.

Looking ahead, the team is planning more educational activities, including additional trauma-informed care workshops and historical knowledge training about Indigenous birthing practices and how labour and delivery and postpartum staff can be allies for patients and families through the birth journey. The team also hopes to gather feedback directly from Indigenous families to understand whether the changes being made are truly creating safer, more welcoming experiences.

“I am hopeful that we are creating cultural safety for our patients and families, but I recognize that will not be for us to determine,” says Michelle. “I often think that by engaging staff (in this work) we're providing a pebble in their own learning journey and the ripples will come from that. It’s going to take a really long time, but I’m optimistic that we can create change.”