Keeping seniors connected

Age is one of several risk factors for isolation

November 21, 2018

By Brenton Driedger, Social Media and Storytelling Advisor, Covenant Health

Cecilia Marion still chuckles when she remembers the bunny who ate so much, she couldn’t squeeze into her clothes.

Cecilia, Senior Director of Operations at St. Joseph’s Auxiliary Hospital and Youville Home, says Youville residents love taking care of their therapy bunny so much, they sometimes get carried away.

“Last year when the carrots came in from the garden, they fed her too many,” says Cecilia, laughing. “And the residents have little dresses they like to put the bunny in, and she couldn’t fit into her dress because she ate too many carrots."

As the carrot supply diminished, Lily the rabbit returned to her normal weight. But Lily’s impact has gone far beyond making a cute story. She has drawn several residents out of their rooms, given them a friend to care for and improved their moods. Cecilia points to the pet therapy program as a shining example of connecting residents to other people and to the world around them.

Many people lose those connections as they grow older, making isolation a real possibility. In 2010, Statistics Canada reported that 16 per cent of seniors felt isolated. Research repeatedly links social isolation and loneliness with poor physical and mental health and shorter life expectancy.

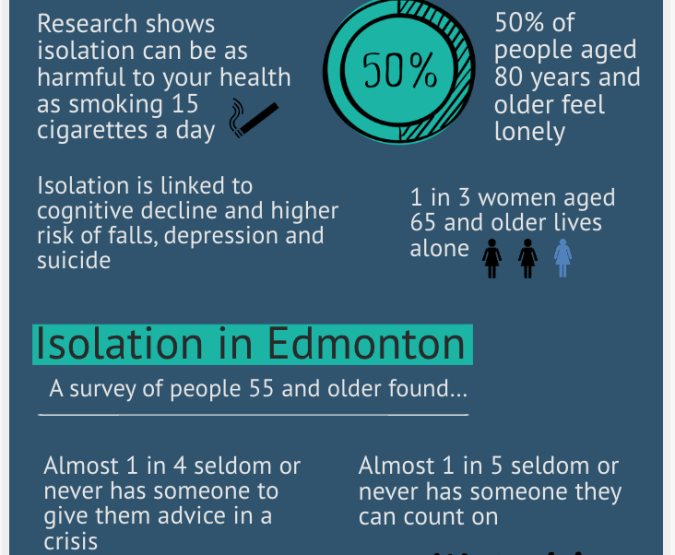

Senior isolation

- Research shows isolation can be as harmful to your health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day

- Isolation is linked to cognitive decline and higher risk of falls, depression and suicide

- 50% of people aged 80 years and older feel lonely

- 1 in 3 women aged 65 and older lives alone

Isolation in Edmonton

A survey of people 55 and older found:

- Almost 1 in 4 seldom or never has someone to give them advice in a crisis

- Almost 1 in 5 seldom or never has someone they can count on

- 24% were considered lonely

Sources: National Seniors Council, Statistics Canada, PEGASIS

The concern for seniors feeling isolated is one that will likely demand more attention as our population ages. In the 2016 census, for the first time, seniors (5.9 million) outnumbered children (5.8 million) in Canada. The gap is estimated to widen by 2031, with 6.6 million children and 9.5 million seniors. Seniors would make up 23 per cent of the population, putting us on par with Japan, the world’s oldest country. Meanwhile, Alberta’s senior population is expected to double to 1.1 million by 2040.

Age is just one of several complex factors when it comes to isolation. Others include gender, poverty and losing supportive family and friends. Geography also plays a significant role, says Scott Stewart, Social Worker at the Edmonton General Continuing Care Centre.

“Canada’s a big country and we have a very mobile population, so individuals don’t have the same connections to their communities of origin that they used to, and families of origin can be quite spread out,” says Scott.

Physical separation can be a factor even when families live in the same community. Women who stayed home to raise children and had a limited social network may find themselves isolated after their children move out and when their spouse dies. Scott says rural residents in particular face a unique challenge as people move away to urban centres and some aging seniors might not be willing or able to sell the family farm.

“But then there comes a point where they can’t get out of the farm because it snowed and they can’t plow their way out and no one’s checking on them,” says Scott.

Winter weather and geography both create challenges for seniors in cities, too. Rachel Weldrick, a PhD candidate at McMaster University, is doing research on the community causes of urban isolation. She sees a common thread emerging: people feel stuck.

“As people age, as you reach 80, 85, 90, there’s a greater chance that you’re going to lose your licence at some point and that seems to be a barrier for a lot of people,” says Rachel.

Rachel says some of the most successful programs for reducing senior isolation involve transportation, such as volunteer drivers taking seniors to their appointments or to the grocery store.

Eating with someone else is also important.

“Food is a social connector,” says Rachel. “Often these meal-based programs end up connecting people really, really well.”

That’s why St. Joseph’s Auxiliary Hospital includes meals in its day program and helps residents find rides there. But it takes things even further, inviting residents to help prepare the food. Both St. Joseph’s and Youville Home host baking programs.

“That’s a very sensory thing because you can take time and smell all the spices that you’re using, and those things really bring back lots of memories and conversation,” says Cecilia. “And if you’re able to do some of that baking up on the units, it makes things smell better, which helps people to want to eat more.”

Many of the activities are designed with groups of people in mind, says Cecilia. The St. Joseph’s day program includes exercises with residents walking around the building. Residents care for plants in gardens at both sites. Along with Lily and the pet program, staff at Youville invite children from an on-site daycare to come upstairs for activities such as drum circles and reading.

“You can just see the smiles and the moods change for people when they get to spend time with the kids,” says Cecilia.

The two centres also emphasize listening to and getting to know each person who lives there. Each resident has a fact sheet that hangs outside their room at St. Joseph’s. It lists their interests, former occupation or things they like to talk about. And a news program enables residents to take up a newspaper, go through the articles and discuss current events together.

Rachel says even small changes can make a huge impact.

“What we know from the research is quality of life can skyrocket, can improve overnight, once we get people connected. People’s general will to live goes up overnight when we’re able to get them connected and help them feel that they have a reason to live.”